Ryan Lochte is a jerk.

That could have been the headline, but it wouldn’t have been newsworthy. We all knew it already. And, oddly enough, that’s probably why his personal brand may very well bounce back from his disastrous night out in Rio during the 2016 Summer Olympics and the series of poorly constructed half-truths that he fabricated to cover it up (Lochte will never be characterized as a master of subterfuge).

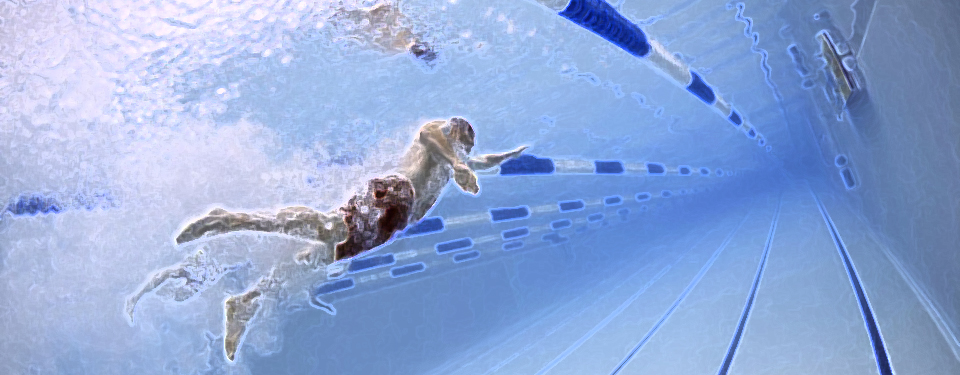

Lochte has spent the last decade or so looking like a wrestling “heel” to Michael Phelps’ heroic “face” (Ted DiBiase to Phelps’ Hulk Hogan). Lochte often comes across as some kind of aquatic frat-boy satire, good looking but shallow, successful but dim, a winner but still constantly jealous of his taller teammate. When people saw Michael Phelps smoking pot they were incensed (“how could he do that to us?”), but if Lochte had been pictured beside him, it probably would have reinforced his own bad-boy image (“no doubt – Lochte made him do it”).

The media has compared Lochte to Lance Armstrong, but the two cases are actually quite distinct. Armstrong was widely known to be a jerk by those who came in contact with him (teammates, competitors, small children, puppies, etc). To the rest of the world he was a shining example of the American way. He beat all of those elitist Eurosnobs at their own game! He overcame cancer! He’s a hero! Armstrong built his Livestrong brand almost completely out of a calculated set of lies that he clung to even as his image circled the drain when we all learned the truth (that he was pathologically dishonest).

In sharp contrast, Lochte has embraced his imperfections. He took part in a reality show that made him look like a vapid meathead and often says things to the press that must mortify his coaches, his agent and his family. His brand is an odd combination of “that guy has it all” and “I would rather hang out with a rabid baboon than Ryan Lochte.” Everybody would love to be him, but nobody feels compelled to meet him.

Consequently, his stupidity in South America is actually brand-congruent. We don’t think less of him because we already believed him to be an idiot. You could make a valid argument that Lochte’s actions are actually beneficial to his brand. After all, he can’t swim for much longer, so why not get a head start on his career as Olympic history’s most famous reprobate? Maybe he can even run for congress!

People who see Lance Armstrong riding his bicycle nowadays subconsciously reach for the car door handle, quietly considering how rewarding it would be to see him tip over into the ditch entangled in his beloved 10-speed. But with Lochte we just sort of shrug and say “he’s no Michael Phelps.” We may not love his brand, but we recognize it for what it is.

Brand equity has been part of American marketing for a century now, and while messaging technology has evolved tremendously, the core of branding has not: be true to your brand, and it will grow to be more than the sum of its parts. Of course, I recommend that your equity is based on quality and innovation and customer service instead of bone-headed shenanigans, but in the end that’s up to you.